Sound, evidence-based regulation is essential to safeguarding consumer safety. Manufacturers must be held accountable to quality-assured safety standards; this applies to both tobacco-derived and synthetic nicotine.

Disclaimer

This article aims to inform adult consumers, health professionals, and policymakers about the differences between tobacco-derived and synthetic nicotine – an emerging product category. The Africa Harm Reduction Alliance has no financial or political interests in the description of these products. We merely wish to fulfil our purpose of educating the public and professionals about the benefits of non-combustible safer nicotine alternatives over combustible tobacco.

Nicotine: A Misunderstood Molecule

Before unpacking the rather niche topic of synthetic versus tobacco-derived nicotine, it is important to acknowledge how significantly misunderstood the molecule is1, among health professionals and the public alike. For example, in 2013, Patel et al2 surveyed 826 full-time faculty members from the University of Louisville’s Schools of Medicine, Public Health, Dentistry, and Nursing. Of the participants, 38% believed that even separate from smoking, nicotine is a high-risk factor for heart attack and stroke. Furthermore, 50% regarded nicotine itself as a moderate risk factor. In another recent US study of 1058 doctors3, the vast majority of them “strongly agreed” that nicotine directly contributes to the development of cardiovascular disease (83.2%), COPD (80.9%), and cancer (80.5%).

These nonfactual misperceptions amongst health professionals are reflected in the consumer population. In 2020, Rajkumar et al4 conducted an international survey of adults who smoke, use THR products, or are previous users of either within the past five years. 54,267 participants were recruited from South Africa, Greece, India, Norway, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Up to 88.7% of current consumers believed nicotine is harmful. Up to 78.0% of respondents believed nicotine is the primary cause of tobacco-related cancer. In six of the seven countries, nicotine was rated nearly as harmful as cigarettes and alcohol.

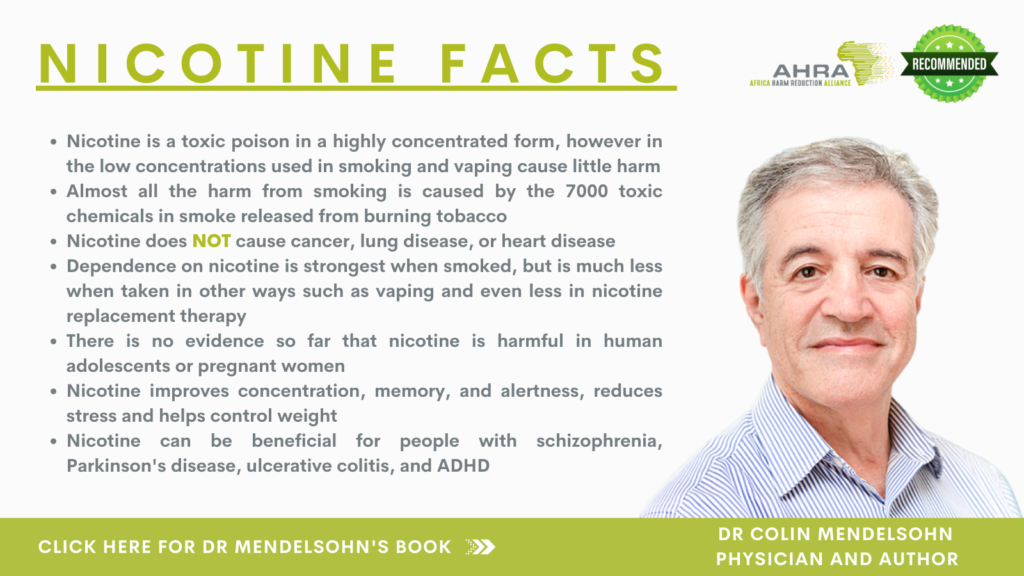

World-renowned physician and pre-eminent expert on nicotine pharmacology, Prof Dr Neal L. Benowitz, has stated1: “Nicotine plays a minor role, if any, in causing smoking induced diseases”. Another physician who is passionate about dispelling myths about nicotine, and helping smokers quit cigarettes is Dr Colin Mendelsohn. He recently published a book “The Healthy Truth About Vaping: Stop Smoking, Start Vaping”5, which is required reading for all health professionals. In the third chapter entitled ‘Busting the Myths About Nicotine’, he lists some key, evidence-based, take-home messages about nicotine:

The History & Chemistry of Nicotine

Nicotine derives its name from Jean Nicot de Villemain1, a French diplomat and scholar, who served as the French Ambassador in Portugal from 1559 to 1561. He had a fascination for the use of tobacco snuff by the Portuguese locals. He sent tobacco leaves and seeds, which originally came from Brazil, to Paris because of the interest in their medicinal use; it was thought to be a remedy for all diseases1. The snuff made from the tobacco plant became quite fashionable in Paris, especially among the rich. Despite centuries of tobacco use, scientists were only able to identify the active ingredient of the tobacco plant in the laboratory during the early 1800s.

Two researchers, Cerioli and Vauquelin, successfully extracted an oily substance from the plant, first naming it “nicotanine” after Jean Nicot1. Later, in 1828, Posselt and Reimann, two researchers from the University of Heidelberg, purified the extract and called it “Nikotin”. In its pure form, nicotine is a colourless or pale-yellow oily liquid. The chemical formula for nicotine, C10H14N2, was established by 1840 and since then, it has been possible to synthesise the compound in a laboratory1.

Stereoisomers: S-nicotine and R-nicotine

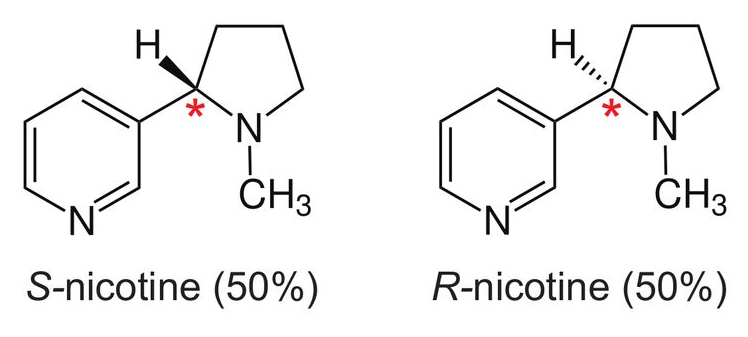

Nicotine is a chiral molecule, meaning that it exists in two forms called stereoisomers: S-nicotine and R-nicotine6. They are identical in chemical formula (C10H14N2), but asymmetrical in structure in such a way that they are non-superimposable mirror images of each other (see diagram below6):

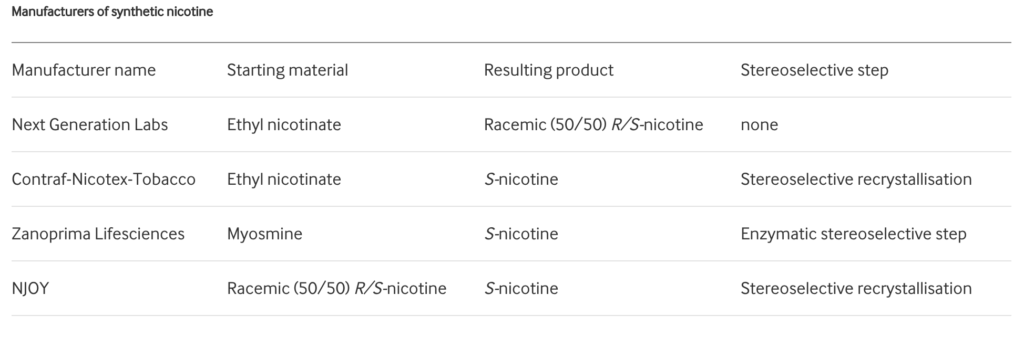

In the diagrams above, reproduced from Jordt’s paper6, the chiral centre of nicotine is labelled with a red asterisk. In tobacco leaf, >99% of nicotine is present as S-nicotine. However, synthetically-derived nicotine (i.e., manufactured in a lab without use of tobacco leaf) contains a racemic mixture, containing both S-nicotine (SN) and R-nicotine (RN). The ratio of SN:RN depends on the manufacturing process, and whether stereospecific strategies to synthesise pure S-nicotine have been used. Jordt’s search6 through Truth Tobacco Industry Documents7 revealed that industry considered using synthetic nicotine commercially dating back to the 1960s, but efforts were abandoned due to high costs and insufficient purity at the time. However, with modern advances in nicotine synthesis, companies are now competing to drive down the production costs of synthetic nicotine6:

Table reproduced from Jordt (2021)6: Manufacturers of synthetic nicotine

What Does USP / ‘Pharmaceutical Grade’ Mean?

You may have noticed on labelling of certain THR products, such as NRT, the letters ‘USP’8 – what do they mean? The letters stand for United States Pharmacopeia, which has an interesting history. The original Greek meaning for pharmacopeia is ‘the art of making drugs’. The need for USP became apparent in the 18th century, when medicines were dispensed in an unregulated fashion by apothecaries, blacksmiths, midwives and others who provided their own versions of popular treatments. Some worked, some didn’t, and some were outright dangerous. Eminent national and medical leaders collaborated to counteract these dangers by publishing the first USP in 1820 – a reference of uniform, quality-assured preparations for the most commonly used drugs8.

Since 1820, the achievement of USP letters have been a key way for manufacturers to demonstrate that their product is quality-assured, pharmaceutical grade purity and potency. In summary, stringent tests require proof of the following to achieve USP status8:

- Identity: the product is what it claims to be

- Potency: it is present in the right amount

- Purity: it is free from impurities, contaminants, or other unwanted ingredients

- Performance: dissolves and disintegrates in the body so the active ingredient can be absorbed

In the synthetic nicotine industry, manufacturers aim to gain market dominance by achieving pharmaceutical grade (USP) synthetic S-nicotine, rather than racemic nicotine mixtures. Another term that is used, similar to USP, is GMP – which stands for Good Manufacturing Practices9. Whilst initially promulgated by the US Food and Drug Administration10, it has also been adopted by the European Medicines Agency (EMA). EMA describes GMP as ‘the minimum standard that a medicines manufacturer must meet in their production processes’, such as the requirement of at least 99% product purity – not containing any fillers, binders, dyes, or other inactive ingredients that serve as a vehicle for active substances9.

The Body’s Metabolism of Nicotine

Nicotine is broken down in the liver by the P450 enzyme system, which is also active in metabolising many other substances. The main metabolised product of nicotine is cotinine, which is excreted by the kidney and can be detected in urine. Nicotine is also secreted in the saliva and breast milk and crosses the placenta, but there is no evidence of it causing harm to pregnant women or their babies1.

The main effect of nicotine in the body is due to the direct stimulation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors that are present in the adrenal medulla, central nervous system and skeletal muscle. The initial stimulating effect of nicotine occurs when stimulation of the adrenal gland leads to the release of adrenaline. In the brain, this stimulation (especially via the dopamine reward circuit) leads to feelings of relaxation and euphoria. It also causes sharpness and alertness1.

Racemic mixtures (containing both S-nicotine and R-nicotine stereoisomers) of synthetic nicotine typically contain about 50% of each stereoisomer6. The physiological effects of S-nicotine in humans are well-understood, due to it being the predominant molecule in tobacco-derived nicotine (>99%). Of note, pure synthetic S-nicotine is chemically indistinguishable from S-nicotine purified from tobacco leaf. However, little is known about the metabolic effects of R-nicotine in humans6. In animal studies, a number of differences have been found:

- The metabolization of nicotine to cotinine differs in kinetics between S-nicotine and R-nicotine11

- In contrast to S-nicotine, R-nicotine did not induce weight loss in rats and did not trigger adrenaline release12

- R-nicotine is a significantly less potent (~10-fold) agonist of nicotine receptors12

Synthetic Nicotine: Regulatory Considerations

Synthetic nicotine manufacturers argue that regulators, such as the FDA in the United States, do not have the authority to regulate their products with the same frameworks used for tobacco products; the manufacturing processes for synthetic nicotine does not involve tobacco leaf. This would enable them to circumvent expensive and arduous processes, such as the Premarket Tobacco Product Application (PMTA). The counter-perspective from regulators is that the alternative would be to regulate synthetic nicotine as a drug, which they already do for nicotine replacement therapy such as nicotine gum, lozenges, and patches6. This has the potential to rule out synthetic nicotine products containing racemic mixtures of S-nicotine and R-nicotine, the latter of which has unknown safety if consumed regularly6. However, this remains the subject of ongoing discussions and there is currently a regulatory gap13.

AHRA’s Position Statement:

- Nicotine is a widely misunderstood molecule. It does not cause cancer, lung disease, or heart disease. There is no evidence so far that nicotine is harmful in human adolescents or pregnant women.

- Smoking-related death and disease is caused by the 7000 toxic chemicals in smoke released from burning tobacco, not nicotine.

- THR products (e.g., nicotine vapes, nicotine pouches) should be available everywhere where smokers can buy cigarettes. This way, consumers have the option, information, and risk communication, to choose safer nicotine alternatives rather than the most lethal option of combustible tobacco, as recently stated by Dr Delon Human at the ATHRF.

- THR products should be regulated in a risk-proportionate way.

- Sound, evidence-based regulation is essential to safeguarding consumer safety, and ousting illicit products. Manufacturers must be held accountable to quality-assured safety standards; this applies to both tobacco-derived and synthetic nicotine.

References

- tobaccoharmreduction.net. An Advocate’s Guide to Tobacco Harm Reduction [Internet]. 1st ed. thr.net; 2021 [cited 2022 Mar 31]. Available from: 1. https://media.thr.net/strapi/d5b691d7b57a532da30f41f52dd63dcc.pdf

- Patel D, Peiper N, Rodu B. Perceptions of the health risks related to cigarettes and nicotine among university faculty. http://dx.doi.org/103109/160663592012703268 [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2022 Mar 31];21(2):154–9. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.3109/16066359.2012.703268

- Steinberg MB, Bover Manderski MT, Wackowski OA, Singh B, Strasser AA, Delnevo CD. Nicotine Risk Misperception Among US Physicians. Journal of General Internal Medicine [Internet]. 2021 Dec 1 [cited 2022 Mar 31];36(12):3888–90. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11606-020-06172-8

- Rajkumar S, Adibah N, Paskow MJ, Erkkila BE. Perceptions of nicotine in current and former users of tobacco and tobacco harm reduction products from seven countries. Drugs and Alcohol Today. 2020 Sep 10;20(3):191–206.

- Mendelsohn C. The Healthy Truth About Vaping [Internet]. 1st ed. 2021 [cited 2022 Mar 31]. Available from: https://colinmendelsohn.com.au/book/

- Jordt S-E. Synthetic nicotine has arrived. Tobacco Control [Internet]. 2021 Sep 7 [cited 2022 Mar 31];0:tobaccocontrol-2021-056626. Available from: https://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/content/early/2021/09/07/tobaccocontrol-2021-056626

- Anderson H. Manufacture of nicotine. British American Tobacco Records. [Internet]. 1964 [cited 2022 Mar 31]. Available from: https://www.industrydocuments.ucsf.edu/docs/#id=lgcy0212

- Quality Matters USP. What the Letters “USP” Mean on the Label of Your Medicine | Quality Matters | U.S. Pharmacopeia Blog [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2022 Mar 31]. Available from: https://qualitymatters.usp.org/what-letters-usp-mean-label-your-medicine

- European Medicines Agency. Good manufacturing practice | European Medicines Agency [Internet]. [cited 2022 Mar 31]. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory/research-development/compliance/good-manufacturing-practice

- International Society for Pharmaceutical Engineering. Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) Resources | ISPE | International Society for Pharmaceutical Engineering [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2022 Mar 31]. Available from: https://ispe.org/initiatives/regulatory-resources/gmp

- Nwosu CG, Crooks PA. Species Variation and Stereoselectivity in the Metabolism of Nicotine Enantiomers. http://dx.doi.org/103109/00498258809042260 [Internet]. 2009 [cited 2022 Mar 31];18(12):1361–72. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.3109/00498258809042260

- Zhang X, Gong ZH, Nordberg A. Effects of chronic treatment with (+)- and (−)-nicotine on nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors in rat brain. Brain Research. 1994 Apr 25;644(1):32–9.

- Coffa B. What is Synthetic Nicotine and is it Regulated? – Enthalpy Analytical [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2022 Mar 31]. Available from: https://enthalpy.com/blog/what-is-synthetic-nicotine-and-is-it-regulated-2/

THR Topics

Popular Posts

Quick Links

Women in THR

Related Posts

Letter to the World Health Organization (WHO)

Letter to the World Health Organization (WHO)

Letter to the World Health Organization (WHO)

Public Health implications of vaping in Germany

Public Health implications of vaping in Germany

Public Health implications of vaping in Germany

Public Health implications of vaping in the United States of America

Public Health implications of vaping in the United States of America